My surname, Kerr, is thought to originate with the Gaelic caerr, which means “left.” Many of my ancestors, the Clan Kerr of Scotland, were left-handed (and I am too), which led to the Scottish expression Kerr-fisted to describe a left-handed person. This trait was beneficial to my ancestors who gained distinction as warriors. In battle, left-handedness is a competitive advantage when most of your opponents are right-handed.

The poet James Hogg (1770-1835) lauded the Kerrs’ prowess in combat. In The Raid of the Kerrs he wrote:

But the Kerrs were aye the deadliest foes

That e’er to Englishmen were known

For they were all bred left handed men

And fence [defense] against them there was none.1

Despite such formidable skills, the Clan Kerr sometimes failed to protect their own. In 1542, an English garrison overtook the castle of Sir John Kerr of Ferniehirst and brutally raped all the Kerr women and their servants. It took seven years to recapture the castle.2 The revenge inflicted by the Kerr men is the subject of Walter Laidlaw’s poem “The Reprisal’ (1549): “So well the Kerrs their left-hands ply/ The dead and dying round them lie….” To my knowledge, however, how the Kerr women and their servants dealt with their histories of sexual abuse never became the subject of lore.

Like me, my mother was sexually abused when she was young. My sister learned this while they watched a Lifetime show about a girl molested by a neighbor. My mom turned to my sister, relayed the events of a tragic evening with as much emotion as she would spend checking off a grocery list, and then turned back to the TV’s blue glow as if nothing had been revealed.

When I remember my mother, who passed away twenty years ago, I sometimes remember myself, barely a teen, contemplating the kind of woman I might become. I looked to her to imagine my possibilities but could only see what I should not be: exhausted and unhappy, as if the life force had been drained from her. I vowed not to follow in her footsteps, not knowing I already shared with her a history of sexual abuse.

I pushed myself hard, trying to avoid her fate. I hoped I would show the world I mattered, regardless of my past. It wasn’t until I felt broken by flashbacks of my abuse in my twenties that I sought professional help. Initially, I felt my need for mental healthcare proved I had somehow failed — that the memories breaking through were signs of weakness, if not insanity. The flashbacks had become so disorienting I could no longer rely on my habit of staying busy to ward off memories. I began to drink alcohol excessively, an effort to push down what I was too afraid to acknowledge and articulate.

Like my mother, I wanted to silence the past rather than deal with my emotions, especially feelings of shame. Yet shame typically becomes more debilitating when it goes unaddressed. A mother’s shame for her history of maltreatment may be the greatest indicator that her children will experience the intergenerational transmission of the effects of her trauma.3 Shame can also be an obstacle to acknowledging you feel unsafe and to seeking support.

Unlike my mother and ancestors, I had opportunities to attend to the impacts of sexual abuse. My generation may be the first in the history of civilization when women can anticipate recovery. Our willingness to commit to self-repair may not only change our lives, but also what we bequeath to future generations.

It matters that we commit to recovery from sexual trauma.

Today my mother would be diagnosed with depression, if not a score of other diagnoses, including complex posttraumatic stress disorder stemming from her childhood as well as posttraumatic stress disorder arising from domestic violence. However, I doubt she would have mentioned the abuse she once suffered to a health provider or psychotherapist, and not all professionals ask. Instead, I imagine they would have seen a woman suffering apathy and sadness, bitterness too, and withdrawn from life.

It is not uncommon to identify a connection between depression and histories of sexual abuse, although I find the diagnosis insufficient and complicit with the silence that often surrounds histories of sexual abuse. It would be more transparent and accurate if women with histories of gendered violence were also diagnosed with oppression (assuming a diagnosis is needed). Sexual abuse is one of the most damaging exploitations of power in part because it is typically perpetrated by someone known to the victim and made possible by either the perpetrator’s role in their victim’s life, social status, or physical strength. These relational dynamics cause a profound sense of betrayal, which is central to how sexual abuse is so traumatizing. Consequently, the effects of oppression must be a primary focus of any diagnosis or plan for recovery.

For example, along with using questionnaires like the Beck Depression Inventory to guide treatment, with its standard items depicting states of depression — “I blame myself for everything bad that happens”; “I can’t make decisions at all anymore”; “I feel guilty all the time”; etc. — the recently developed Oppression-Based Traumatic Stress Inventory could also be used, which addresses the effects of oppression, including identifying “reoccurring, unwanted distressing memories about discrimination-related experiences”; “avoiding certain types of people because you worry they will behavior in a discriminatory way”; and, “viewing yourself in a more negative way because of discrimination.”4 I suspect the word “discrimination” could easily be replaced with “sexual abuse” without changing the purpose or reliability of the score. Making shifts to include the effects of oppression on mental health is significant and necessary because it means seeking different solutions than simply ingesting a pill and managing a chronic illness. Rather, it means taking seriously the necessity of addressing the long-term consequences of relational dynamics that exploit and abuse.

Whereas some think of depression as primarily a biological disease, my mom surely passed on more to me than her genes. I also inherited from her the effects of her history of oppression, especially how she dealt with her trauma. Studies suggest a mother’s need to dissociate her own history of sexual abuse increases the likelihood she won’t identify the signs that abuse has happened or is happening to her daughter.5 I believe this was true of my mother. I also believe I unconsciously learned from her to dissociate feelings and memories that threatened to overwhelm me and to ignore my body and soul’s reaction to abuse, using substances to dull the pain until all I felt was numb.

Since the 1970s, researchers have known of the existence of methyl groups that “tell” DNA which genes to transcribe in response to environmental influences, including how a person coped with trauma. These methyl groups are referred to as epigenetic tags. Whereas DNA, as the fundamental material of life, remains unaltered across the lifespan, the presence of these epigenetic tags alters the expression of our genes. As a result, traumatic events and conditions not only recalibrate the basic physiologic systems of the person who experienced trauma, their altered physiology can be passed to offspring. Perhaps this is why my mother’s tendency to dissociate also became my primary defense against remembering trauma. Perhaps this is also true for the many generations of women before us who also survived sexual abuse by dissociating its effects. It is profound to imagine how much our bodies, and the bodies of past generations of women, have been shaped by societal conditions of oppression.

Even if a woman was not sexually abused in early life, she nevertheless is at greater risk for rape in adulthood due to the mental health and trauma histories of the caregivers in her childhood home and how they dealt with their unresolved trauma. According to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, many forms of childhood adversity can increase the likelihood of sexual abuse later in life. The ACE study began as a survey of patients at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego, CA, that queried about adverse childhood experiences, including emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, witnessing their mother being battered, household substance abuse, mental illness in the household, parental separation or divorce, and/or an incarcerated household member. ACE scores are derived from the number of adverse experiences an adult experienced during childhood. For women with an ACE score of zero, and thus no history of adverse childhood experiences, only 5 percent were raped in adulthood. However, for women whose ACE scores were four or greater, 33 percent had been raped as adults.6 Even when sexual abuse does not occur in childhood, if multiple adverse experiences were present there may have not been opportunities to develop the healthy beliefs and behaviors necessary for protecting oneself from harm. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume many ACEs arise from the adversity and distress of parents’ or caregivers’ early lives and their lack of opportunities to addresses their unresolved trauma.

One of the fundamental developmental tasks of childhood is gaining from our interactions with caregivers the capacity for self-regulation of emotions. Developmental psychologist Allan Schore claimed this is the task of early life development: “in infancy and beyond, the regulation of affect is a central organizing principle of human development and motivation.”7 Emotions are a primary way our bodies express their physiological states, relaying to ourselves and others whether we are peaceful, joyous, lonely, or afraid. As infants, we lack a developed prefrontal cortex necessary for discerning meaning and make thoughtful choices. Instead, we rely on our emotions and bodies to understand the world and on our caregivers to shape our experiences. Optimally, as infants and young children we have ample opportunities through our relationship with caregiver(s) to learn how to regulate our emotional reactions to external and internal stimuli that might otherwise feel overwhelming.

Often a healthy attachment relationship is described as a caregiver who can act as a safe base when an infant or child is frightened or overwhelmed. If we were fortunate, our caregivers neither harmed nor frightened us, and we could rely on them to comfort and protect us, thus serving as a safe base. However, many of us with histories of sexual abuse in the first decades of life were abused by those who should have protected us. Many of us also experienced other adverse childhood experiences. We thus lacked a caregiver who consistently could be the safe base of attachment and now, as adults, we are tasked with becoming a good enough parent for ourselves.

Yet attachment isn’t just about learning how to regulate our emotions in response to threat, but also how to navigate the world of play and exploration, which also involves heightened, complex emotions that become the basis for living a dynamic life, one that challenges us to reach our highest potential. The idea of attachment as a “safe base” is but one side of a dynamic interplay of extremes. The other side is the ebullience of joy and the drive to explore that arise through play and discovery. Learning to modulate these emotions is necessary for meeting challenges and reaching our highest potential. Schore observed: “Attachment is not just the reestablishment of security after dysregulating experience and a stressful negative state, it is also the interactive amplification of positive affects, as in play states.”8

The bond between infant and caregiver, like those witnessed between other mammals and birds and their offspring, is a training ground for modulating and expressing emotions, each encounter an opportunity to expand possibilities. Loving care is the alchemical crucible that encourages us to excel yet also protects us when we find ourselves outside the bounds of safety. When all goes well, we learn to trust love and cope with novelty, both in the environment and our inner worlds, emerging from childhood with a foundation for greater emotional complexity and self-regulation as we continue to grow and develop.

In the earliest years of life, an infant feels indistinguishable from her caregiver, and in essence, self-regulation begins as co-regulation. In moments of healthy attachment, a resonance develops between caregiver and infant as facial expressions are reciprocated while breath, heartbeat, and nervous systems synchronize. Through a felt sense of oneness, the developing infant learns the natural oscillations of emotions, how they both rise and fall. Emotions become anchored in a sense of reality as something encountered and shared with another. What the caregiver can tolerate the child also has an opportunity to discover how to tolerate. Through supported containment and amplification of emotions, the child discovers her preferred homeostasis, where she feels most emotionally comfortable, and also how to cope with unfamiliar and stressful situations. The outcome is a resilient adult capable of adapting to ever-changing circumstances, including her inner world.

The lack of secure early life attachment due to adverse childhood experiences, including a caregiver with unresolved trauma, can result in a limited capacity for coping with stress due to lack of opportunities to explore the boundaries of one’s own emotional range. Emotions that overwhelm the caregiver have a high likelihood of overwhelming the developing child. What our caregiver(s) cannot feel, including the parts of themselves and emotions they dissociate, we also have increased likelihood of dissociating. In effect, we inherit from them their emotional limitations. Schore observed the consequences include, “lack of variability when … faced with environmental demands that call for alternative choices and strategies for change.” The outcome, he claimed, is “a poor capacity for change [and] a limited ability to continue to develop at later points in the life cycle.”9

I witnessed this in myself when flooded by flashbacks of sexual abuse. I was easily overwhelmed by emotions attached to these memories. I also didn’t trust others to be supportive in part because I lacked co-regulation experiences around intensely frightening emotions. It was not something I thought of as possible. Instead, I isolated and tried to numb my emotions with substances, perhaps in part because I had witnessed similar behavior in my mother. Like her, I dissociated the emotions that threatened to overwhelm me, at least until I no longer could.

Before I worked through my unresolved trauma, many of my aspirations were hindered by traumatic stress, thus impacting my development. It took a lot of reflection (and therapy) for me to understand how my relationship with my emotions were shaped by my mother and her trauma, that in her need to protect herself from her own emotions, I too was predestined to silence what threatened to overwhelm me. I do not blame her. On the contrary, I still feel deep sadness for how she was treated and the suffering it caused her. I also perceive my responses to my trauma as part of my epigenetic inheritance from her, if not other women in my ancestral past. So many of us suffer the consequence of patriarchal abuses of power, which insidiously alter the bond between mother and child.

There are many ways we give voice to trauma without expressing what happened. Trauma-focused psychotherapist Janina Fisher observed, “the symptoms tell the story better than the ‘story’.”10 Some of the common ways trauma is communicated include:11

• Depression • Irritability • Loss of interest in things once enjoyed • Numbness • Decreased ability to concentrate • Insomnia • Emotional overwhelm • Loss of sense of the future • Hopelessness • Shame and worthlessness • Little or no memories of the trauma • Nightmares • Flashbacks • Hypervigilance • Distrust • Panic attacks • Chronic pain • Generalized anxiety • Headaches • Substance abuse • Eating disorders • Feeling unreal, out of body • Self-destructive behavior • Process addictions • Suicidal ideas and/or actions • Lost sense of “Who I am” • Dissociation • Passivity • Loneliness, alienation • Problems with anger

Some of these reactions begin as ways to cope with ongoing abusive and oppressive situations and people. For example, feelings of shame and self-hatred can keep us compliant to ongoing abuse; self-harm and suicidality can be ways to gain a sense of control; and irritability and anger are useful for keeping people away.12 Tragically, early adaptations to traumatic situations continue to show up in our lives, along with other symptoms of trauma, influencing our sense of self, how we relate to others, how we perceive the world and our place in it, as well as our ability to accomplish goals and create a meaningful life.

Fortunately, unlike my mother’s generation and those before her, we don’t have to accept the above signs of unresolved trauma as the inevitable outcome of a history of sexual abuse. Nor may we need to be diagnosed with mental disorders as chronic conditions to be endured, or “managed,” throughout our lives. Rather, through trauma-focused interventions we begin to witness and resolve how our abuse histories continue to organize our bodies, beliefs, emotions, and relationships in our present lives.

Much of the work of trauma-focused recovery involves purposefully and mindfully redirecting attention away from traumatic reminders and the states of dysregulation they cause. It also involves opening oneself up to play, exploration, and joy. Regardless of the nature of our early life attachment experiences, as adults we can develop and expand the skills of self-regulation. Doing so not only supports your reasons for committing to recovery, but also can bring a greater sense of aliveness and possibility when you are no longer overwhelmed by fear and anxiety. The rest of this article looks at the neurobiology of defense and practices for increasing self-regulation. Through these practices you gain greater control over the direction you want your life to take rather than repeatedly being redirected by traumatic reminders.

The Polyvagal Theory and Increased Self-Regulation

One of the best ways to reduce trauma triggers is to address them at the source of their origination: the unconscious defense responses activated when internal stimuli (e.g., emotions, body sensations, memories) and external stimuli (e.g., persons, places, or circumstances) remind us of the trauma. This vital, “bottom up” aspect of recovery work is supported by neuroscientist Stephen W. Porges’ polyvagal theory that addresses how humans and other species have evolved to deal with threats.13 The polyvagal theory takes an evolutionary perspective on the role of the autonomic nervous system in defense against threats. Porges revealed that when it comes to the defenses that have led to the greatest likelihood of survival, the human capacity to rely on relationships — that “safe base” of attachment — has garnered the most success.

The autonomic nervous system is a bundle of nerves connecting the brain to the body. It controls bodily functions necessary for survival, including respiration, circulation, digestion, and elimination. The autonomic nervous system influences defense reactions by altering and organizing these bodily functions to support either fighting, fleeing, or submitting to a threat, or alternatively, seeking support from others. For instance, when the body organizes for escape or defense, blood is redirected to large muscles, such as to the legs for fleeing or to the arms for fighting, while blood flow is diverted from other functions like memory consolidation or digesting a meal. Similarly, through the complex physiology and musculature that make possible vocalization and facial expression, we have evolved to relay to others our distress, and thus seek support to survive threats.

Early description of the function of the autonomic nervous system described it as divided into two subsystems: the sympathetic nervous system that mobilizes the body in support of fight or flight and the parasympathetic nervous system that slows or shuts down body functions during states of submission. Porges’ polyvagal theory incorporates this traditional understanding of the organization of the autonomic nervous system while adding a crucial evolutionary lens that extends this model to include a third defense response: the social engagement system and our evolved capacity to use voice, facial expressions, and emotions to relay to others our need for help. According to Porges, there are two separate branches of the parasympathetic nervous system: the ventral branch responsible for social engagement and the dorsal branch activated during times of immobilization or submission to a threat.

Porges identified a hierarchy existing between the three subsystems of the autonomic nervous systems. The most evolved defense response is the ventral parasympathetic nervous system, or social engagement system, and the capacity to seek secure people for protection. This can be thought of as the defense of attachment, which is first activated and shaped through the co-regulating dynamic established with caregiver(s). In a perfect world, where we lived in supportive, loving families and communities and never had to submit to sexual abuse, we could scream or cry for help knowing people were nearby to protect us. The social engagement system, when not primed for defense, is correlated with the optimal zone of arousal, which is a physiological state of well-being.14

The next most evolved defense reaction activates the sympathetic nervous system and mobilizes the body for fighting off a threat or fleeing from it. We may also freeze when we do not know what to do yet still experience high levels of energy as our bodies ready to fight or flee. The least evolved defense occurs when fighting or running from a threat are not perceived possibilities and there is no one to protect us. Then the dorsal branchof the parasympathetic nervous system is activated, resulting in immobilizing defense responses such as collapsing or cowering in the face of threat. We may also freeze when we realize there is no possibility of escaping harm. This has been referred to as “paralyzed terror.” It is thought to involve both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems as the body is primed for action (sympathetic), nevertheless completely immobilized (parasympathetic) without hope of escape.15 All of these defense responses are activated unconsciously. Thus, we do not choose our initial reactions to threat. Instead, our body chooses for us.

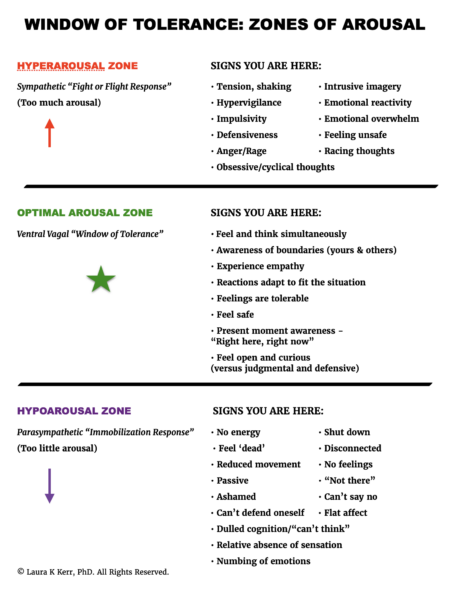

Rather than referring to the different branches of the autonomic nervous system, some trauma-informed psychotherapists speak about states of hyperarousal (sympathetic nervous system) and hypoarousal (dorsal branch of parasympathetic nervous system) when our bodies unconsciously organize for defense in response to traumatic reminders. Many of the signs of these defense states are also present in the previous list of trauma-related symptoms. This overlap between trauma symptoms and states of hyperarousal and hypoarousal speaks to the nature of unresolved trauma: we are often reacting defensively to situations, people, and our own internal states in our efforts not to be hurt again.

Hyperarousal, as related to the mobilizing defense response, is the high activation that occurs in our bodies when it organizes to fight or flee perceived danger. Signs of hyperarousal include:

- emotional reactivity

- emotional overwhelm

- tension and shaking in the body

- defensiveness

- racing thoughts

- intrusive imagery

- obsessive thinking

- impulsivity

- fear

- anger

- rage

The hyperaroused mind and body is primed to act in response to a world perceived as dangerous. The heart races, blood pressure rises, and the body tenses when scanning for threat or in response to stimuli that provoke trauma-related remembrances. States of hyperarousal can cause headaches, insomnia, gastrointestinal problems, physical pain, and heightened sensitivity to sound and touch. Hyperarousal can also involve difficulty focusing and sustaining attention, and it can include problems processing language and coordinating movements.16 Rather than relaxing into the tasks of daily living, the body and mind are tense and bear the burden of vigilantly searching for threat.

The hyperaroused mind and body also take more risks. When repeatedly flooded with flashbacks and nightmares, it is not unusual to think and act as if danger is inescapable and is the overarching nature of reality. There is greater likelihood of hyperactivity and impulsivity as the unconscious continually scans for threats. When hyperaroused, violence toward others or harming oneself, including suicide attempts, are also greater risks. It may also feel as if the only way to regulate all the pent-up energy is to abuse substances or processes.

When hyperaroused, we tend to be distrustful and quick to anger. Time spent with others may easily become overwhelming. Especially when hyperarousal is ongoing due to unresolved trauma, there may be a tendency to anticipate relational discord, if not also feel fearful of being harmed by others. The tendency is to feel easily rejected or slighted by the words or actions of others. Alternatively, some seek intense relationships that mirror or help sustain the state of hypervigilance that over time becomes associated with maintaining safety. Yet in hyperaroused states, we have difficulty reflecting on our own behaviors and responding thoughtfully to others. Instead, the intensity and speed at which our bodies are primed to defend can cause us to be reactive and often insensitive. Relaxing and enjoying peace in relationships may feel difficult, or even anathema, to the neurobiological drive to remain alert and vigilant.

All these reactions are driven by the sympathetic nervous system and are attempts to cope with the unconscious preparing of the body for protective action. When trauma is unresolved, and we lack skills for regulating our defense responses, there’s greater likelihood our orientation toward threat will lead to unhealthy or dangerous attempts to discharge the pent-up tension in our bodies that can harm ourselves and our relationships.

In contrast to hyperarousal, hypoarousal, as an immobilizing defense, involves states of low to no arousal. When we feel there is no option but to submit, we begin to mentally and physically “check out.” Signs of hypoarousal include:

- numbness or absence of sensation

- muted emotions or emotionless

- profound lack of energy

- reduced physical movement

- disconnection from body and environment

- difficulty saying no or resisting what feels threatening

- difficulty with cognitive processing

- passivity

- shame

- low self-worth

- depression

States of hypoarousal often involve feelings of guilt. Memories of having shut down in response to sexual abuse can contribute to a painful spiral of self-recrimination for not doing enough to stop the abuse. However, there are multiple reasons for becoming immobilized. According to founder of sensorimotor psychotherapy Pat Ogden, common reasons include: being overpowered and not having the physical strength to defend yourself; not having ample time to fight or flee or doing so would have made the situation worse; conflicted feelings for the perpetrator; the threat of retaliation; and previous traumatic or oppressive experiences conditioned you to respond with immobilizing defenses.17 Some of us were too young, naive, or trusting to even understand that what was happening constituted abuse. When we blame ourselves for our natural reactions to sexual abuse, we increase trauma symptoms, especially shame. Trust you did the best you could in the circumstance, even make this a mantra — It’s not my fault. I did the best I could — to begin resisting the spiral into self-blame, guilt, and shame.

Frequent states of hypoarousal are likely to lead to a diagnosis of depression, one of the most common diagnoses women receive. Hypoarousal shares many symptoms with depression, especially low self-worth, shame, difficulty with cognitive processing, disconnection from one’s body and the environment, and low energy. Unfortunately, getting diagnosed solely with depression can be a missed opportunity to understand how neurobiology is altered by sexual abuse and what can be done to recover from the effects of sexual trauma. This happened to “Victoria”:

Victoria, who suffered from early sexual abuse, complained of a lifelong pattern of being withdrawn, “spaced out,” and unable to sense her body or emotions. She reported that her previous therapist diagnosed her with depression and prescribed antidepressants. Victoria had developed action tendencies [habitually activated defense responses] that kept her in a hypoarousal zone: She described herself as “passive,” with difficulty initiating action, and reported that she spent long periods of time sitting on her couch “spacing out.”18

Victoria developed ways of coping with trauma-related stress and flashbacks in much the way she had survived her abuse: through states of hypoarousal. In states of passivity, she was less likely to upset an out-of-control perpetrator; and when “spacing out,” she was shielded from overwhelming, intrusive stimuli. When triggered by traumatic reminders, she returned to the state of hypoarousal that kept her alive when she was young, but tragically kept her body reliving the trauma in adulthood.

Victoria’s reactions are common. Especially if you were a child when the abuse happened, submission is almost guaranteed, especially if the perpetrator was also a caregiver. As trauma psychologist Pat Ogden and colleagues observed, “it is inevitable, given their dependent status and developmental vulnerability, that children will submit to abuse at least until the adolescent years.”19 Yet this can leave us fearful of many experiences and relationships that implicitly require trust. As a result, there is often a tendency to either self-isolate or feel emotionally “cut off” from common life experiences in attempts to cope with traumatic stress.

When submission, as an immobilizing defense response, is repeatedly activated, such as when childhood sexual abuse is ongoing, the body is likely to habituate this defense in response to feeling threatened or unsafe. For many of us, such as “Petra,” hypoarousal may seem to infiltrate all aspects of our lives:

Petra’s incest experiences were much more debilitating because her submission defense turned into a longstanding habituated response pattern. She continued to feel a frequent sense of “collapse,” a tendency to “give up” under relatively minor stress, a loss of enthusiasm, an absence of joy in living, and a lack of direction about her future. Her tendency toward hypoarousal continued into adulthood and prevented her from achieving her potential psychologically, occupationally, and socially.20

When submissive body states and their corresponding emotions become habitual, they may act as cues to would-be perpetrators that submission will be the likely response to an assault. Ogden and her colleagues wrote: “individuals who do have a history of abuse might have become immediately hypoaroused, engaging the immobilizing submissive defense in the same situation, especially if submission was the habitual and predominant defensive response to their past threat.”21 Thus, self-defense experts recommend to walk confidently, with head up and back straight, and actively scan for danger, since these are signs of a person capable of activating defense responses such as shouting for help, fighting, or fleeing an assault. However, this advice can be difficult to take if a strong, upright posture itself feels threatening when historically your safety depended on a collapsed spine, hunched shoulders, and eyes averted, which cumulatively are likely to relay to a perpetrator an expected state of submissiveness. Furthermore, many of us grow up in cultures where women and girls are expected to be — and look — submissive. It takes time and practice to become comfortable with more active defense responses, such as a strong, upright posture and vocalizing need for support. Fortunately, change is always possible, regardless of how long ago the abuse occurred or how much our bodies unconsciously adapted to the possibility of further threats.

Understanding our defense reactions and altering them is important to responding effectively to current threats. Because unfortunately, in the face of reminders of past victimization, most of us instinctively react with old defenses, including submissive body states and emotions that interfere with healthy boundaries and self-protection. Furthermore, in response to sexual abuse we also form beliefs about relationships and societal norms that might have been accurate of the conditions and the perpetrator(s) of sexual abuse, but might cause unnecessary avoidance and alienation as we attempt to avert further harm. Intimacy and emotional closeness can be frightening after sexual abuse. Learning to discern when our defenses are activated by prior traumas versus an accurate appraisal of current conditions and relationships is foundational for living a full life.

Especially when sexual abuse occurs during the first decades of life, it can contribute to detachment from emotions in general, thereby eliminating an important source of information about the environment, including the ability to appropriately gauge if a person or situation is safe or if someone is a potential threat, and thus the need to activate the social engagement system and seek help, or mobilize defenses while there is still an opportunity to fight or flee harm. We can find ourselves repeatedly trusting the wrong people just because our bodies have habituated to oppressive people and situations. Hence it is important to develop self-regulation skills and resuscitate a full emotional life following a history of sexual abuse, including learning how we personally respond to threat, whether real or perceived.

Window of Tolerance

Existing between the extremes of hyperarousal and hypoarousal is what psychiatrist Daniel J. Siegel labeled the window of tolerance, those times when defense responses are not activated and we are receptive to healthy social engagement.22 This is also referred to as the optimal zone of arousal and is associated with traits that contribute to sociability, such as empathy and the capacity to connect with others and share meaningful pursuits. The window of tolerance is where we can approach life with curiosity instead of feeling excessively judgmental or defensive. It is a more present-focused state in which feelings are adapted to the situation that is unfolding rather than in reaction to traumatic reminders. This optimal zone of arousal is perhaps best characterized as the capacity to feel safe within oneself, in one’s environment, and in relationships with others. I also think of it as like the ideal outcome of co-regulation with a caring attachment figure — except we give it to ourselves. There is another bonus: when in your window of tolerance, you are more likely to achieve your goals and live the life you desire.

It is not uncommon for people with complex trauma and maladaptive attachment histories to feel uncomfortable with feeling good and living within the window of tolerance, at least initially. When you frequently are hyperaroused or hypoaroused, feeling safe and regulated often feels like a lucky reprieve rather than the beginning of a new norm. You may feel as if you are nevertheless waiting for something negative to happen, and thus proof you are still unsafe (and should not really believe in the possibility of change). It takes time for the body to adjust to feeling safe and excited about life without underlying anxiety that the rug is going to be pulled out from under you just when you finally think it is okay to relax and trust the process of change. Even once you do adapt, living well does not mean never feeling defensive. Rather, the process is one of learning how to distinguish signs you are safe from signs you are in danger, letting go of defensiveness when it is not necessary for survival. This is a skill to be developed that must be continually practiced. However, when you commit to identifying when you are out of the window of tolerance and use skills to return to states of emotional regulation and well-being, these practices become the foundation for transformational change.

The process of getting into the window of tolerance is fairly straightforward. We resolve or lessen states of hyperarousal and hypoarousal and “return” to the window of tolerance by following a three-step process that involves:

1) learning the signs that defenses have been activated,

2) witnessing when defenses are activated, and then

3) utilizing self-regulation techniques to reduce or eliminate distress.

These three steps are a central practice for resolving trauma-related distress. What may distinguish someone who is doing well compared to someone who is overwhelmed by traumatic reminders is their capacity for self-regulation. Having a maladaptive attachment history (and possibly a high ACE score) increases the likelihood of posttraumatic stress, regardless of when the trauma happened, unless you later develop skills for self-regulation and utilize them when you identify that you are responding defensively to benign situations.

To reduce and resolve traumatic stress, we must form the habit of directing attention toward stimuli we want to react to, rather than what historically we paid attention to through the unconscious drive for safety. Although we cannot gain absolute control over our unconscious processes, we certainly can “tame” them by consciously redirecting our attention. This is more likely achieved when we use techniques for working through states of hyperarousal and hypoarousal. Click here to download my quick guide (in English or Spanish) for addressing states of hyperarousal and hypoarousal and returning to the window of tolerance. Most of the exercises take at most a few minutes and are easily incorporated into your day. They either work with the body or the breath, which are two of the best pathways to reducing traumatic stress and increasing self-regulation. By using exercises in this guide, you begin to reduce traumatic stress by learning how to identify the signs that defenses have been activated, witnessing when they are activated, and then using self-regulation techniques to reduce or eliminate your distress — that three-part process of developing self-regulation: learn, witness, regulate!

The exercises work best if you practice using them before you find yourself outside the window of tolerance. This increases the likelihood that your body will remember how to execute them as well as anticipate the relief they can provide. It also helps to bring a feeling of playfulness to practicing the exercises. Think of practicing as priming yourself for feeing good or better when you find yourself hyper- or hypoaroused. In effect, your body and breath start to become a safe base you return to when feeling overwhelmed.

Defense responses are largely unconscious, and thus we cannot control them. I know I said that before, but I feel it is important to repeat because so many of us blame ourselves for our instinctive reactions to trauma. Yet, by being gentle with ourselves — being curious rather than judgmental — we can notice when our defenses are activated in nonthreatening situations, such as when we experience a flashback, and then use skills to reduce our stress and regain a sense of well-being. In this way, we learn to regulate our reactions to what unconsciously threatens us. The wonderful benefit of regularly practicing self-regulation skills is that we get triggered less and less, and when it does happen, we more quickly regain well-being.

Of course, defense reactions are not always bad. On the contrary, they are necessary for survival. When trauma is still unresolved, we are not flawed but rather need to learn how to discern between when feeling defensive is justified and we need to protect ourselves versus when self-regulation skills are needed. In our high-stress world, this is a skill that is vital even when we feel our trauma is resolved. We all can benefit from learning how we uniquely defend against what threatens us. Learning our individual defense responses can go a long way in gaining self-mastery and lead to less self-blame and greater self-compassion when feeling threatened.

Many with unresolved trauma spend a lot of time in defensive states, alternating between hyperarousal and hypoarousal, with little time spent in the window of tolerance. The “bottom up” approach of working with breath and body found in the Window of Tolerance guide helps stop swings between states of hyperarousal and hypoarousal, extending time spent in the window of tolerance — what is sometimes referred to as widening the window of tolerance. The increased sense of safety that results acts as a foundation for both leading a life without the chaos of an overreactive defense system and with greater focus on creating the life you desire.

The window of tolerance can also be a tool for thinking about what we want to pass on to future generations. As a child, my mother’s body, the emotions she expressed, as well as the one’s she hid — including from herself — had a profound influence on my development, including how I originally distinguished between what counted as “winning” at life and what meant I was failing. I often thought my mom was losing at life despite outward appearances of success; her body told me she was unhappy even when she smiled. Like a friend’s son once said to her, “Mom, I know you’re smiling, but your heart is crying inside.” Taking the time to attune to your body and emotions and learning how to alleviate or diminish defensive states is one of the greatest gifts you can give to the people you love and who love you.

But it’s not just for the people in your life. When we fail to address chronic defense reactions, we risk grave harm to our bodies. Sexual trauma contributes to autoimmune disorders, heart disease, cancer, hormonal disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain, asthma, and diabetes. Because the likelihood of revictimization is so high for survivors of sexual abuse, by midlife a woman may have had multiple experiences of being abused and oppressed, along with the chronic health problems to prove it. You deserve to be healthy and happy.

The habit of not listening to the body until it screams with pain or illness is one many of us learned from our mothers, aunts, and grandmothers. Jungian analyst Cara Barker recalled:

My own mother, at times of stress, advised my sister and I to “rise above it.” Unfortunately, her effort to teach us to extricate our focus from pettiness was heard as “discard your body wisdom.” Many women of her generation, and my grandmother’s, were advised to do likewise. This has caused us to lose contact with instinctual knowing. The fact is, we cannot transform if we leave out our body. We need our physical body to partner with our spiritual body if we are ever to feel whole.23

Our daughters, nieces, and younger friends, whether they are in our present lives or in our futures, deserve to witness generations of women become more enlivened as life goes on, not less so. We deserve this too.

Yet many of us feel guilty for not giving more to our families, jobs, and communities, that we should be more and do more for others. Perhaps much of the guilt we feel is because we know we should value ourselves more and the gift of life that we have been given. Like Barker wrote, “the deepest level of guilt, of course, stems from not taking responsibility for living life to the fullest.”24 Many of us have learned being a woman requires ignoring what our bodies and souls need to thrive. Part of the struggle of overcoming oppression by patriarchal expectations is discovering how we can both be true to ourselves and authentically share ourselves with others.

When we too busily serve the needs of the world, our bodies and souls show signs they are being cheated, whether through illness, exhaustion, or the many symptoms of unresolved trauma. When we try to excessively achieve, we leave little room for the slow meandering of creativity, the unfolding of instincts, and listening to body wisdom. The same consequences are found when we feel we must escape the burden of fear and live a life too small for us. For to be fully alive, we must seek engagement with the world and with ourselves, often in equal measure. We must learn to let go of defenses and trust in relaxation, play, and the pleasures of being alive.

When we feel broken from abuse, beaten down by life, that’s when we need radical self-care. We need to mother ourselves and create a sense of containment and safety in our bodies so we can rekindle the joys of living. Getting good at feeling joy is one of the best ways to protect yourself. When you start regularly living within your window of tolerance and trust feelings of safety and joy, you will more often notice when you enter defensive states of hyper- and hypoarousal around certain people and in certain situations. This is valuable information. Sometimes it is a sign you need to engage more in the reparative work of recovery. However, as you become more aware of when you are triggered and why, your defenses also become more accurate measures of the need for boundaries and self-protection in certain relationships and environments.

I’m so fortunate to have inherited my mom’s smile, her sense of charity, her love of dance, the arts, and music. Yet I still feel heartache for my mom because she never got to be her whole herself, integrated and living within her window of tolerance. Here she might have found the missing peace.

Activities for your consideration:

• Prioritize taking care of your physical health. If you haven’t had a physical examination or basic screenings in a while, including dentistry, please visit a clinic or see your doctor(s).

• Read my Living Within Your Window of Tolerance guide. Identify which of the signs of hypoarousal are most likely to apply to you. Do the same with hyperarousal. Next, identify 2-4 ways to engage with your body when hypoaroused and 2-4 ways to engage with your body when hyperaroused. Don’t wait until you’re hyper- or hypoaroused to practice them. Instead, practice them until they feel like second nature. You can also write them on a small piece of paper that you keep with your wallet or in an electronic note on your smartphone, so they are with you when you need them. These exercises are especially helpful at transition points in your day (e.g., between work and home). Make a point of regularly returning to your body to check in with yourself.

• On paper, in your journal, or in an online document, get in the habit of reflecting on how the window of tolerance exercises impact you by responding to the following five prompts in response to episodes of hyperarousal and hypoarousal:

1. What was the upsetting event?

2. Were you hyperaroused or hypoaroused (see the diagram)? Both at different times?

3. Using the window of tolerance diagram, identify the symptoms/signs that apply to you.

4. Which intervention(s) did you use?

5. What changes did you witness? How long did it take until you felt back in your window of tolerance?

It can sometimes take quite a while to get back in the window of tolerance. So do not judge yourself if it takes longer than you expect to resolve your distress. Give yourself the gift of time.

• At some point in your recovery, consider taking a self-defense class. Look for specific programs geared toward women with histories of gendered violence that also have resources for emotional support during the course. These courses can be overwhelming and cause flashbacks, although they can also be transformative. Most self-defense classes, especially if they involve “model mugging,” are best taken after you have created sufficient safety and stability in your life and have skills for addressing states of hyper- and hypoarousal. Anticipate you will need more self-care and support as you go through any self-defense course. If you are working with a psychotherapist or other type of trauma-specialist (which I always encourage), consider using your therapy to process what comes up for you.

While reading this article, what came up for you? Thoughts? Emotions? Memories? Images? Body sensations and/or movements? Just notice the type(s) of reactions you had without getting caught in the content, which is a fundamental skill for dealing with trauma.

References

1 This poem and “The Reprisal” by Walther Laidlaw (below) were mentioned in Dan Zambonini’s 2010 blogpost “Clan Kerr and The Legend of The Spiral Staircase,” on The Januarist: Past Vs Present. Accessed January 21, 2014. URL: http://www.thejanuarist.com/clan-kerr-and-the-legend-of-the-spiral-staircase/.

2 Iain Gray, Kerr: The Origins of the Clan Kerr and Their Place in History (Glasgow, Scotland: Lang Syne Publishers Ltd, 2011).

3 R. L. Babcock Fenerci and A.P DePrince, “Shame and Alienation Related to Child Maltreatment: Links to Symptoms Across Generations,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 10, no. 4 (2018): 419-426.

4 Samantha C. Holmes, Daniel Zalewa, Chad T. Wetterneck, Angela M. Haeny, and Monnica T. Williams, “Development of the Oppression-Based Traumatic Stress Inventory: A Novel and Intersectional Approach to Measuring Traumatic Stress” Frontiers in Psychology 14, no. 1232561 (Oct 24, 2023).

5 Karlen Lyons-Ruth, Lissa Dutra, Michelle Schuder, and Ilaria Bianchi, “From Infant Attachment Disorganization to Adult Dissociation: Relational Adaptations or Traumatic Experiences?” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 29, no. 1 (2006): 63-86.

6 Bessel Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Viking, 2014), 146.

7 Allan N. Schore, “Effects of a Secure Attachment Relationship on Right Brain Development, Affect Regulation, and Infant Mental Health,” Infant Mental Health Journal 22, no. 1-2 (2001): 9-10.

8 Schore, 21.

9 Schore, 16.

10 Janina Fisher, “Advanced Seminar Level II Program 2010-11, Mindfulness and Neuroplasticity,” 3.

11 Janina Fisher, “Psychoeducational Aids for Working with Psychological Trauma, 8th Ed.

Watertown, MA: Center for Integrative Healing, 2009.

12 Pat Ogden, Training for the Treatment of Trauma (Boulder, CO: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute, 2007).

13 Stephen W. Porges, The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2011).

14 Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clare Pain, Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy (New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2006), 29.

15 Ogden et al, Trauma and the Body, p. 94.

16 Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, 158.

17 Ogden, Training for the Treatment of Trauma.

18 Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clair Pain, Trauma and the Body, 39.

19 Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clair Pain, 97.

20 Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clair Pain, 104.

21 Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clair Pain, 99.

22 Siegel, Daniel J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are.Second ed. New York: The Guilford Press, 2012.

23 Cara Barker, World Weary Woman: Her Wound and Transformation (Toronto, ON: Inner City Books, 2001), 70.

24 Barker, 84.