Prior to entering college, some women choose not to pursue majors in male-dominated fields like STEM, economics, and philosophy if they anticipate gender discrimination. For those who persevere, having professors sensitive to gender issues can protect against the impact sexism can have on emotional well-being, the ability to focus on studies, and future performance. Unfortunately, such mentors are often rare in male-dominated fields.

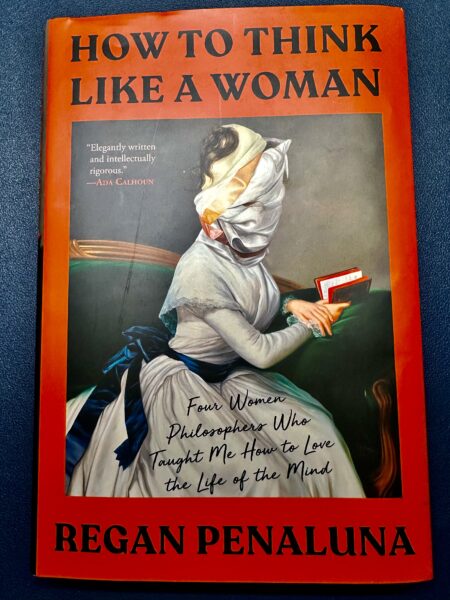

In How to Think Like a Woman, Regan Penaluna recounts her experiences as a graduate student in philosophy and the devastating impact sexism had on her psyche, relationships, and career. She begins her book with a recollection of betrayal by her favorite male professor, someone she thought of as an ally and who once praised her talent as a scholar. Penaluna was one of only two women in his crowded symposium on Plato’s Republic when the topic turned to “The Female Drama.” Her once cherished mentor began to explore what he assumed was a foregone conclusion: women’s inferiority to men as philosophers.

“I want to start with a request, I remember him saying. His voice was loud, and he looked ahead at no one but spoke to everyone. Our job, he said, is to make sure we aren’t letting custom get in the way of truth. Then he asked: Why is it women have not achieved the highest level of thought? That there are not many women in philosophy departments and haven’t been throughout time? It might be politically correct to assume our culture has prevented women from taking on these roles, he offered, but it might not be philosophically sound.”

Penaluna recalls her professor seemed proud of what he said, if not courageous for challenging what he perceived as political correctness. Yet his remarks left her only with confusion and self-doubt. Did he not think she was intelligent? Was she an exception to his rule? In a larger context of devaluation and harassment, his remarks seeded Penaluna’s spiral into low self-worth, isolation, and eventually depression – a heavy burden to carry in addition to the rigors of graduate school.

The diagnosis complex trauma is typically reserved for chronic childhood abuse and/or neglect, and with it, the profound feelings of betrayal that are a distressing aspect of interpersonal trauma. However, there is increased recognition that ongoing conditions of oppression in adulthood can lead to the same outcomes. I believe complex trauma not infrequently results from the sexism and racism that plagues many in graduate school and early professional careers, contributing to reduced numbers of women and people of color in leadership positions in academia and other male-dominated fields.

Penaluna chronicles the impact sexism had on her psyche and performance. She began to doubt the quality of her work, speak less in the classroom, and withdraw from faculty and peers. Penaluna eventually sought help from a mental health provider and was prescribed medications for anxiety and depression. She discusses the benefits she received from medications and therapy, although they were never enough to quell her self-recriminations.

Her treatment was at least a partial failure on the part of the mental health system, in my opinion. More needs to be done to distinguish mental disorders from the effects of oppression and complex trauma. For example, along with using questionnaires like the Beck Depression Inventory to guide treatment, with its standard items depicting states of depression — “I blame myself for everything bad that happens”; “I can’t make decisions at all anymore”; “I can’t do any work at all”; etc. — the recently developed Oppression-Based Traumatic Stress Inventory could also be used, which addresses the effects of oppression, including “reoccurring, unwanted distressing memories about discrimination-related experiences”; “avoiding certain types of people because you worry they will behavior in a discriminatory way”; and, “viewing yourself in a more negative way because of discrimination.” This shift to including the effects of oppression on mental health is significant and necessary because it means seeking different solutions than simply ingesting a pill and managing symptoms. This is ultimately what Penaluna did by writing How to Think Like a Woman.

Penaluna devoted her graduate education to researching women philosophers generally ignored by Western philosophy’s canon. How to Think Like a Woman incorporates this research, sharing the histories and ideas of several women philosophers, including Mary Astell, Damaris Masham, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Catharine Cockburn. Their stories are intertwined with Penaluna’s memoir of how these remarkable women became her role models for overcoming the wounds of patriarchy.

I found myself thinking of the radical wisdom of the late antipsychiatry scholar Bonnie Burstow who advocated that “trauma work move more in the direction of critical adult education, with counselor and clients co-exploring the traumatizing and oppressive situations and structures together and clients taking up real tasks.” In Penaluna’s case, her “counselors” included some of the world’s greatest women thinkers and her “real task” is sharing openly about the consequences of sexism in education and the impact that a lack of intellectual community has for defining oneself as a scholar. She writes:

“My intellect wasn’t shaped in the glory of transcendent questions but rather in response to the insidious systems of oppression. In this sense, I am a woman thinker.”

Near the end of her book, Penaluna mentions Christine de Pizan who lived during the fourteenth century and wrote the novel, The Book of the City of Ladies. In this novel, de Pizan includes a fictional Christine who reads a book chronicling the sexist ideas of poets and philosophers. For fictional Christine, “a great unhappiness and sadness welled up in my heart, for I detested myself and the entire feminine sex, as though we were monstrosities in nature.” She is then visited by the ghost of Lady Reason who tells her to write her own book, which, like a city, “will be a populated place, an intellectual refuge where women can visit … and be inspired by other women’s examples, so they will never again forget themselves in the sea of men’s disparaging words.” How to Think Like a Woman is such a metropolis, recounting the lives of numerous inspirational women — including Penaluna — revealing the resilience, if not exhilaration, that can emerge when oppression is resisted and challenged.