A defining attribute of humankind is our imaginations. They make possible thriving in almost every climate and grant us the ability to create ecospheres where none existed. If we notably differ from other species, then our uniqueness is found in the time and energy we devote to imagining alternatives to the conditions we inhabit. Whereas other species also rely on tools and symbolic behavior, and thus have imaginations too, they nevertheless depend as much, if not more, on embodied, relational awareness. As we moderns move toward greater reliance on tools like smart phones as intermediaries between our mindscapes and the world around us, the less we feel our connection to Earth, each other, and the species with whom we share our planet.

Because of how we use our imaginations, it is a tragedy of our times that so many live in impoverished conditions that obstruct meaningful communal involvement and sever interdependency with the natural world. This is opposite of indigenous, archaic communities that were the forebearers of imaginative living. From them we inherited our extended dependency on care to reach full maturity, the emotions we feel and express, and the lifelong tension between self-expression and group belonging that defines so much of the human drama. There is a particular quality to this imagination, witnessed in the centrality of play for development, the making of art to relay wonder and awe, and the reliance on rituals to integrate psyches and communities. For those who study the deep history of humankind, our indigenous ancestors represent humanity’s golden age.

We’ve squandered this inheritance. Their imaginative weaving of embodied ways of relating with a nature-based worldview have been replaced by widespread manipulation of information, objects, and people in pursuit of what those in power imagine the world should be, which frequently is constructed without regard for the natural world, communal bonding, or how our bodies evolved. Some may believe ingenuity makes us more brilliant than our ancestors. However, without their ways, we forfeit the surest path to some of life’s greatest rewards: feeling part of a unitive creation, unus mundus, the joy of knowing we are never alone, and the exuberance of freedom.

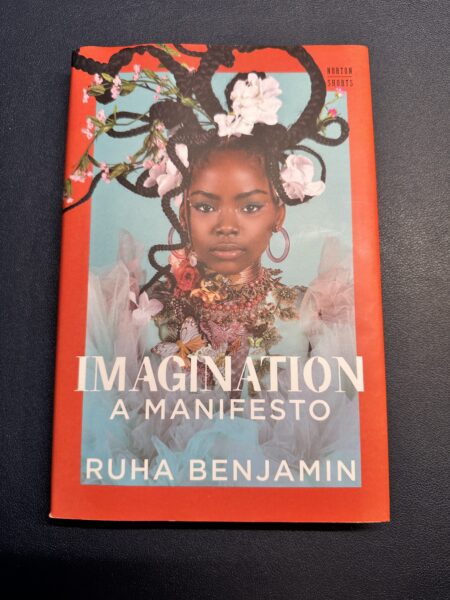

Sociologist Ruha Benjamin’s Imagination: A Manifesto articulates the social cost of losing what some call the indigenous way of life — a culture centered on care, creativity, and connection with nature — and its replacement with a quest for technological utopias more fairyland for the chosen few than a truly inclusive society. For Benjamin, it is “a eugenic way of imagining the world, wherein some places and people are deemed inherently inferior and thus requiring domination,” and “has justified colonialist expansion, slavery, and genocide.” She acknowledges:

“We do not usually think of our contemporary society as eugenic. But look closer … from who gets access to scarce resources when hospitals don’t have enough supplies for all patients, to who gets warehoused in U.S. jails because they cannot afford bail, some lives are deemed desirable and others disposable.”

I think of Jungian analyst Anthony Stevens’ idea that there are two archetypal systems driving the formation of societies: one “concerned with attachment, affiliation, care giving, care receiving, and altruism, and the other “concerned with rank, status, discipline, law and order, territory, and possessions.” One makes us healthy, happy, and whole in self and community, while the other drives competition, stress, alienation, and disregard for basic human needs and life itself. Benjamin’s manifesto is an attempt to shift our collective imaginative powers toward a care-centered worldview before it’s too late.

Benjamin identifies an inflection point when U.S. society seemed to grapple with these alternative ways of imagining societal possibilities. Quoting W.E.B. Du Bois:

“Two theories of the future of America clashed and blended just after the Civil War: the one was abolition democracy based on freedom, intelligence, and power for all men; the other was industry for private profit directed by an autocracy determined at any price to amass wealth and power.”

This quote captures the struggle Benjamin witnesses and chronicles in Imagination. Whether looking at schools, technologists, IQ tests, consumer credit, prisons, video games, lack of spaces and opportunities to play, weaponry, or border walls, she identifies the repeated failure “to regenerate imaginaries and futures that greed and power snuffed out.”

Schools, the very places tasked with mental and social development, are one of the first spaces many of us experience a dampening of our capacity for imagining alternatives to the dominant worldview. Research suggests that when students start kindergarten, they typically score as geniuses regarding divergent thinking, tested by the ability to imagine a variety of uses for common objects like paperclips. However, the capacity for divergent thinking is virtually “schooled out of them” over the next decade.

Typically, reduction in creativity scores is translated into potential loss of future innovation. However, Benjamin argues the biggest risk is the failure to address “the historical mission of our time”: “an honest reckoning with the existing stratification of humanity.” Rather than the threat to keeping our country and economy competitive, Benjamin focuses on the implications of loss of ingenuity for our collective moral imagination, such as when schools lack spaces to learn about diverse cultures that might seed “a solidaristic imagination.” Benjamin is neither anti-science nor anti-technology. Rather, she advocates for “[populating] our imaginations with images and stories of our shared humanity, of our interconnectedness, of our solidarity as people….” There is a particular genius that arises from understanding how to foster webs of relationality that we need as much as cutting-edge technologists.

A central issue explored by Imagination is who defines human nature and how they use that definition to maintain a hierarchical society. The relatively small part of the world’s population who own most of the resources has an outsized influence on how the future is imagined. Benjamin observes, “those who monopolize resources monopolize imagination.” This sobering insight resonates with her critique of an imagined future based on space travel and AI made by followers of “radical longtermism” in which one goal is a future of “transhumans” who use technology to transcend natural limitations of the body, if not reach some technologically mediated version of eternal life.

Dreams of near endless life and escape to pristine planets would be possible for only a few. For longtermists, their imagined utopia is worth ignoring the environmental and social problems so many presently suffer, which will only get worse if we fail to radically reimagine societal norms and expectations and our relationship with Earth. Benjamin quotes Ethiopian-born computer scientist Timnit Gebru:

“They don’t ever want to talk about real issues they might by implicated in, like racism, sexism, or imperialism. They want to talk about grand visions of saving humanity… wanting to feel like a savior and not wanting to feel like a problem.”

Gebru’s observations are underscored by the following quote from longtermist Nick Beckstead that Benjamin also shares:

“Saving lives in poor countries may have significantly smaller ripple effects than saving and improving lives in rich countries. Why? Richer countries have substantially more innovation, and their workers are much more economically productive.”

This is an excellent example of what Benjamin considers a failure of moral imagination.

Benjamin’s book is short (part of the Norton Shorts series) yet long on examples, especially of the consequences of failing to imagine institutions and relations centered on care and equality rather than power and profit. She also shares inspiring efforts to reimagine and foster a compassion-driven, equitable society. Benjamin presents indigenous communities as a central model, along with her own creative suggestion: the lifeways of bees. Her book includes a useful appendix with prompts individuals and groups can use to reimagine their work for a care-centric world.

Much of what we have inherited from our earliest ancestors is left withering and underdeveloped in our modern lives. Nevertheless, we can learn to imagine, grow, and live as humans once did, before the natural world became other to our human-made landscapes. Our good fortune is the reawakening of histories and cultural practices that can act as our guides. However, first we may need to reimagine our understanding of human nature, as Benjamin contends, and end the long history of exploitation that led to the current era.

References

Benjamin, Ruha. Imagination: A Manifesto. Norton Shorts. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2024.

Stevens Anthony. The Two-Million-Year-Old Self. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1993.