According to a 2014 World Health Organization Report, and data from one hundred thirty-three countries representing eighty-eight percent of the world’s population, nearly one in five women were sexually abused in early life. Yet only a third are thought to have told anyone, not even a friend. In silence many blame themselves for the abuse, just as communities and societies often do.

Those with histories of early life sexual abuse have been cast as too seductive, too naive, out too late, or too solitary in their excursions into public and private spaces. They have been judged as suffering from impoverished character and poor judgment. They have also been pitied and typecast as victims forever scarred by an unimaginable horror. They have intuited, if not known, what journalist Parul Sehgal observed: “Those who have faced sexual violence are so commonly sentimentalized or stigmatized, cast as uniquely heroic or uniquely broken. Everything can be projected upon them, it seems — everything but the powers and vulnerabilities of ordinary personhood.”

Compared to other forms of adverse childhood experiences, those sexually violated during the first decades of life are also at greater risk for substance use and abuse, which increases the likelihood of cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and liver disease. They are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, engage in suicidal actions, and exhibit symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. They are also more likely to have histories of high-risk sexual behaviors and contract sexually transmitted diseases. Reflecting on a longitudinal study of sexually abused girls conducted in the United States, Bessel van der Kolk writes:

“Compared with girls of the same age, race, and social circumstances, sexually abused girls suffer from a large range of profoundly negative effects, including cognitive deficits, depression, dissociative symptoms, troubled sexual development, high rates of obesity, and self-mutilation. They dropped out of high school at a higher rate than the control group and had more major illnesses and health-care utilization. They also showed abnormalities in their stress hormone responses, had an earlier onset of puberty, and accumulated a host of different, seemingly unrelated, psychiatric diagnoses.”

The consequences continue in adulthood, when women with histories of early life sexual abuse are more likely to experience sexual revictimization. One study concluded up to seventy-nine percent of women sexually abused as children were later raped as adults. When abuse was perpetrated by a family member versus a non-relative perpetrator, the likelihood of revictimization was greater.

The amount of shame a survivor experiences increases the likelihood of revictimization. Women with high levels of shame are more likely to be sexually revictimized than women with lower levels of internalized shame associated with the sexual abuse or those who lack histories of sexual abuse.

Following sexual abuse, the fear of being shamed can be debilitating. According to researchers Heidi La Bash and Anthony Papa, trauma-related fear is not always associated with the fear of further physical harm, as research on traumatic stress presupposes, “but instead can be related to threats of social judgment, stigma, or ostracism.” Both fear of physical harm and of being shamed contribute to withdrawal and avoidance of reminders of the trauma. Both also contribute to traumatic stress and increase the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress disorder.

When communities and families fail to protect girls and teens from sexual victimization or fail to respond with appropriate support when abuse does occur, many will blame themselves if this can give some small measure of control over an overwhelming experience. Without support, the tendency is to avoid confronting what happened and the lingering consequences on mind, body, and spirit. Yet avoidance increases the likelihood of inner fragmentation and self-destructive fantasies, beliefs, and behaviors, which further impair the ability to seek help. In this cycle of distrust and alienation, many lose connection to their own minds and bodies as well as to relationships and communities. The tragic consequence is that without anyone to share their feelings of overwhelm, confusion, and distress, survivors of early life sexual abuse are more likely to engage in addictions, suicide attempts, eating disorders, self-mutilation, and other self-destructive behaviors, which further fuel shame and alienation.

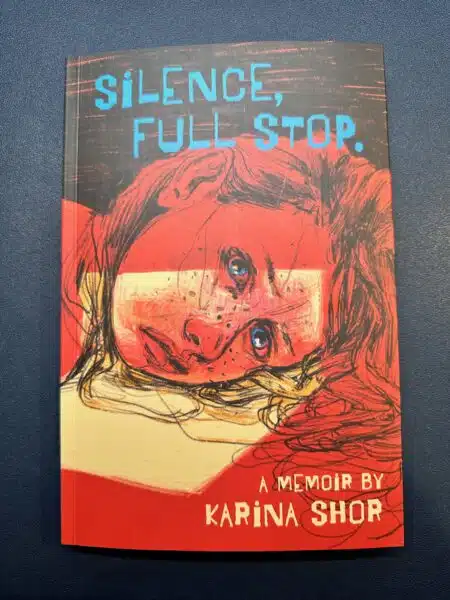

Karina Shor’s illustrated memoir, Silence, Full Stop., gives voice to how a silenced history of childhood sexual abuse can lead to profound self-destruction. Shor’s memoir begins with one of her first childhood memories: immersed in dark ocean waters, “disconnected from the world, my mind goes clear.” This becomes a metaphor for her need to escape her body and overwhelming emotions following childhood sexual abuse, an urge that sets Shor “at sea” within herself and the world as she repeatedly searches for that escape. Shor tells the story of a child growing up as an outsider who becomes a teenager dealing with the angst that plagues so many on the journey to adulthood – except that her early life was tragically driven off course by a childhood molestation.

Shor’s Silence, Full Stop. is the bravest and most visceral account of the descent into self-destruction following childhood sexual abuse that I have ever read. The images are provocative, yet the language is simple, often poetic, and searingly honest. Shor shares deep insights that act as turning points in her story, revealing how quickly and dangerously a belief can alter the course of a life. For instance, when flashbacks emerge as Shor begins to navigate the unfamiliar landscape of adolescence, she writes:

“Maybe this is the real coming of age, forgetting what really matters and focusing on the waves of sensation flowing through my body.”

And so, her life turns away from the “normal” teen trajectory into a disorienting chaos of self-destruction as she tries, on her own, to confront emotions and body sensations stemming from the trauma. Shor combines her inner life observations with undiluted imagery of how ugly life can become when you completely devalue your self-worth and no longer feel anyone can understand you or even care what you are experiencing.

Most societies want women like Shor to remain silent about their sexual abuse histories — certainly not story their experiences — even when sexual abuse is recognized as an atrocity and a crime. Without intention or conscious awareness, most children mirror society’s reactions and follow its norms, both explicit and implicit, for how to respond to the incomprehensible events in their lives. This is how many of us learn to avoid remembering events in our past that might threaten our sense of self, worldview, and the status quo. If the adults in our lives don’t talk about it, then we learn not to mention it too.

Yet sexual abuse is so profoundly destructive to the self-concept and feeling like a human being that it rarely hides quietly in the mind’s deepest recesses. Even if sexual abuse isn’t spoken about, it isn’t truly silent. Like Shor reveals, memories of early life sexual abuse can fuel a rebellious descent into situations unconsciously associated with the abuse as people, substances, and contexts become like props in a play, revealing a truth that otherwise cannot be expressed.

Some psychotherapists describe these recreations as repetition compulsions or acts of triumph, depending on their psychological heritage. They are seen as efforts to draw attention to what happened, articulating what cannot be voiced, or alternatively, re-enacting past conditions to discover a different outcome, this time triumphing when once the only option was submission. Whatever the motivation, they are also driven by an archetypal drive to heal, no matter how misdirected the efforts might be.

At the time of a trauma like sexual abuse, when defenses take hold and fragment mind and body, the opposite also takes root: an expectation to feel safe and whole again. Unconsciously, something in us waits to feel peace and to be nourished by loving people. Even after years of repetition compulsions or would-be acts of triumph, there is still this rhizome waiting to move in directions of growth. Like the detritus of a long winter becomes mulch for the first efforts in spring, Shor concludes, “and now, let it go.” We all can foster growth of the survivors among us. We must only witness, accept, and be ready to listen.

References

Bash, Heidi La, and Anthony Papa. “Shame and PTSD Symptoms.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 6, no. 2 (2014): 159-66.

Banyard, Victoria L., Linda M. Williams, and Jane A. Siegel. “The Long-Term Mental Health Consequences of Child Sexual Abuse: An Exploratory Study of the Impact of Multiple Traumas in a Sample of Women.” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, no. 4 (2001): 697-715.

Kessler, Bonnie L., and Kathleen J. Bieschke. “A Retrospective Analysis of Shame, Dissociation, and Adult Victimization in Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 46, no. 3 (1999): 335-41.

Sehgal, Parul. “The Forced Heroism of the ‘Survivor’.” New York Times Magazine, May 8, 2016, MM13.

Shor, Karina. Silence, Full Stop. Brooklyn: Street Noise Books, 2023.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking, 2014.