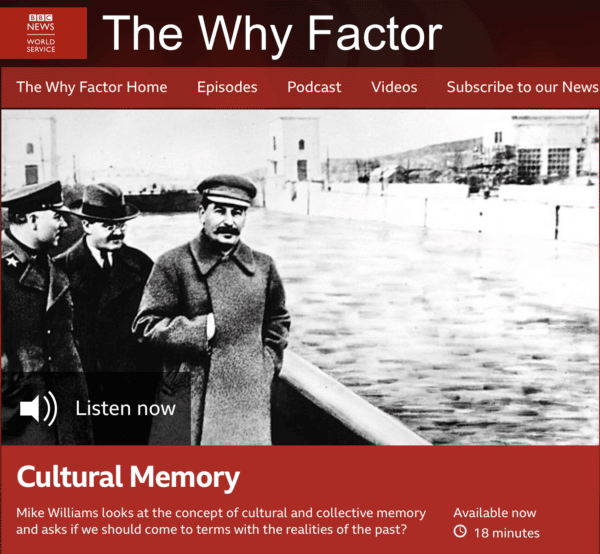

BBC’s The Why Factor has a short podcast on trauma well worth your time (18 minutes).

Cultural Memory explores how societies respond collectively to traumatic memories of war and extreme human rights violations, which too often involves silencing memories or entirely rewriting history.

Controlling narratives of past atrocities is frequently about maintaining or establishing power. As an example, the podcast looks at how aggressors invent narratives that attempt to erase memories of human rights violations, which, because of fear of retribution, people uphold as truth regardless of their own opposing memories.

The podcast makes the case that forgetting trauma may not be as much a psychological reaction as a political one. Such “forgetting” can go on for as much as thirty years. Often, it’s not until a younger generation feels hampered by past generations’ silences that an alternative perspective of reality emerges, one not weighed down by denial of the past.

Cultural Memory questions if remembering trauma contributes to healing, and at least one person interviewed believed asking people to dredge up memories of human rights violations causes unnecessary pain. I certainly understand his sentiment; it’s hard to watch people suffer. Yet fear thrives in silence, and the extreme power differentials that lead to human rights abuses thrive on both fear and silence. There are also less painful ways to remember the past than narrating traumatic events, such as somatic therapies and other trauma-focused methods that are less concerned about what happened and more focused on alleviating suffering and creating a better future. In the quest for truth, there are sensitive ways to balance individual needs with collective justice.

Traumatic stress is an intergenerational phenomenon. Our fears and defenses can be passed to subsequent generations. Our unresolved traumas can encumber their efforts at living without the consequences of trauma. Today, there are methods for recovering from trauma’s effects that were not available to past generations.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy generally identifies three stages of recovery: creating safety, addressing traumatic memories, and reintegration of one’s personhood, if not also rejoining with one’s community. Recalling traumatic memories, and grieving their impact, comes later in the therapeutic process — well after emotional regulation and distress tolerance are established. Fortunately, there are ways of remembering that are less painful than others. How we remember is sometimes as important as what we remember.

Originally published 2013/03/08

Revised 2022/03/09

© Laura K Kerr, PhD. All rights reserved (applies to writing and photography).